The Making of the Omani Kumma

The Kumma (كمة) or Kuffiyeh in other Arabic dialects, is an essential headpiece for all Omani men, one that is worn daily.

During last Eid I realised I always struggled in finding a design that aligns within my criteria of: fit, colour and pattern. Eventually settling for a best-case compromise.

Yet the older Kummas, those I remember from childhood and old photos of our family, appeared consistently well designed. When I inquired my mother about it, her answer was simple well-known fact: all Kumma’s were custom made. Only in recent decades did production shift toward machine-made or mass-produced versions, often manufactured abroad in South or East Asia for competitive pricing. Most of the younger generation, including myself, grew up unaware of the gradual degradation in quality, even in hand-sewn quality.

My mother showing my brother and I the quality details of Kumma

Admittedly, this information and article might not be new information for Omanis, but my background information on my own culture is minimum; as I excuse myself of having lived abroad for nearly a decade, but it’s not good excuse - considering later realising my own hometown is one of the hubs in Kumma making.

Therefore I decided to understand the local manufacturing process of the Kumma, not necessarily academically, but through participation. This article is not a definitive historical reference; nor the correct “terminology”, as there are more comprehensive sources elsewhere. Instead, this is my own designer’s study of a cultural fashion/clothing piece — learning by doing, observing, and engaging the process.

What is the Kumma?

The Kumma is an intricately embroidered men’s headpiece that carries both cultural significance and personal identity. Its exact origin remains debated (either Omani or East African, reflecting the deep historical exchange between these regions). Kummas were always hand-embroidered by women within the family, often worked on intermittently over the course of a year, and completed in time for Eid. A fully handmade Kumma could cost up to 300 Omani rials (≈ USD 750) and lasts decades of daily use.

While earlier versions were typically embroidered in a single colour on white cotton calico, contemporary interpretations sometimes use two or more colours.

The Making of a Kumma

Phase I: networking

Before any stitching begins, one must first find the Master/head Kumma Coordinator (there should be an Arabic term for it?); often an elder woman and master craftswoman who oversees a network of embroiderers within her neighbourhood or village. She knows who is currently available, who is busy with other commissions, and their experience level (which affects the price). Most of these women nowadays work on Kummas part-time, balancing family life, careers and other responsibilities.

Traditionally, this network is accessed simply by asking an elder in the family. It was both ironic and reassuring to discover that one of the most respected Kumma networks is based in my hometown of Quriyat within the capital region, and the head coordinator was none other than my father’s aunt. Until the first step is started, we coordinated with her on the task of making 2 Kumma’s, and the availability of an embroiderer.

Phase II: Design & base

For the pattern, I started by studying existing Kummas, paying close attention to the geometric patterns and the way colours complemented each other. Traditional designs often feature repeating motifs, floral elements, or geometric shapes. I opted to use two patterns I love, the Arabic “Waw” letter, and the Timurd Tri-foil pattern. As I have yet to see any in any Kumma. These patterns will take form in the structural base of the Kumma’s two fabric components: a circular crown, and a rectangular band.

This stage requires a specialist Kumma-tailor who prepares the base by reserving the pattern areas while filling the remaining surface with thick white cotton calico. Such tailors aren’t as popular as the dishdasha tailors, but can still be found in older parts of Muscat, particularly in Muttrah, after asking around tailor shops. I then brought to him a printed visual and patterned references below. Rather than dictating every detail, I trusted the tailor’s experience to interpret balance and spacing.

I was expecting him to be surprised by the use of Arabic lettering, but he was actually unimpressed; as he showed me prototype pencil drawings of several not-legal complex designs that aren’t allowed in public, due to an Omani law that regulates Kumma’s where logos and full names are not allowed on the Kumma. So it does not degrade its cultural quality (hence they are probably used privately or for decoration).

After measuring my head, he took a month to complete the base. Starting with a sketched pencil drawing on the structures, then going over them with the stitching machine. This process costed me around 9 OMR for both designs.

The printed reference give to the Kumma base tailor, left the Timurid trefoil, right the Arabic letter “waw”

Base layer in process, where I passed by the store mid-way in the month and found him working on it

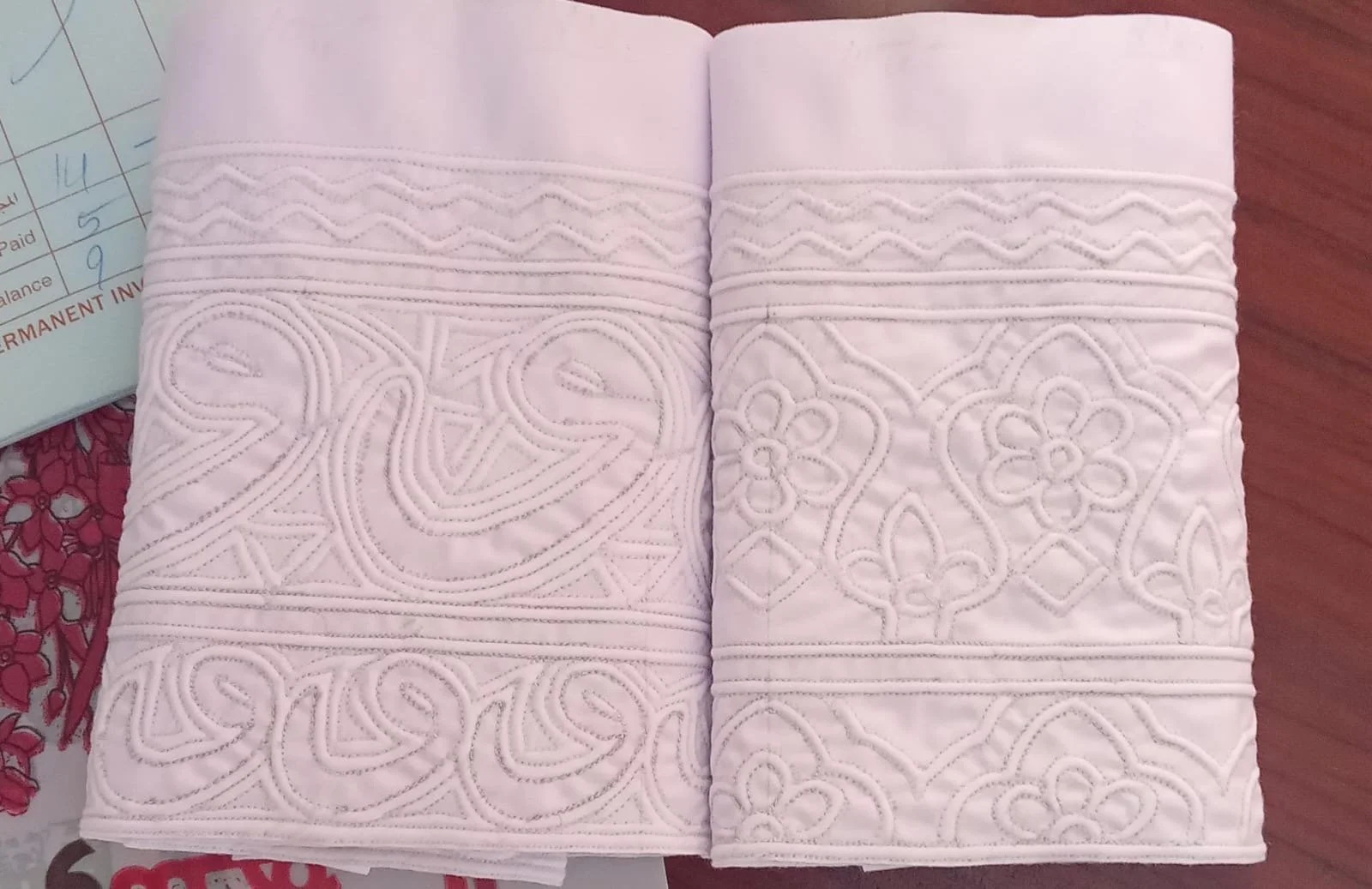

Finished base layer

Phase III: colours and delivery

My mother provided a decades-old thread sample and suggested I search Muttrah souq for the colours I need. Asking simply for “Kumma threads” led me to the right shops almost immediately in the first alleyway near the main entrance of the souq. I learned that the original threads that my mother provided are no longer produced. Historically, each star was embroidered using double passes of fine thread, a process that doubled the time required. Today, thicker double-threaded alternatives are used instead.

I was given a colour catalogue from a manufacturer called Dima, but with unfortunately limited availability in colour range. From what’s available, I selected two tones closest to my favourites. Once I acquired it, I bundled each Kumma with colour threads in preparation for the delivery.

The delivery is rarely direct nor with a set time: it goes from a family member to another, through a subtle chain of hands when families meet and greet and exchange gifts - stretching from house to house, then city to city, until it reaches the embroiderer’s home. This could take a few days to a month. But it was something I was briefed early by my mother on the long process.

The two colours I have chosen

Phase IV: star stitching

The most important and longest part of the Kumma process is beautifully called Tanjeem (تنجيم) or star stitching. Which involves adding star-shaped (circular) stitches in the empty spaces left from base tailor. The smaller, more delicate, and cleaner the stars, the longer the process takes and the pricer the Kumma becomes.

The Head Kumma coordinator assigned my Kumma’s to an embroiderer based on availability and skill level. And I was fortunate to be matched with someone who was available, reducing the timeline significantly. And she took around 4 months to complete each set, which is considered quick. Taking into consideration that my Kumma’s were intentionally made with a cleaner, minimal pattern.

My Kumma in process of being embroidered

Payment after this stage is complex; particularly due to my semi-direct engagement and the involvement of family networks. The cost of each kumma is approximately 100 OMR (± 30 rials, depending on the density of star embroidery). Typically, the coordinator proposes a price, but now the embroiderer offers a lower rate, and the buyer—myself in this case—opts to transfer a slightly higher amount directly to the embroiderer, in order to ensure the best compensation for the labour. This arrangement represents an uncommon inversion of market dynamics, in which the seller underprices the work and the buyer compensates beyond the suggested amount. Again, it might be due to my very indirect familial relation with everyone involved.

The completed embroidery of one of my Kumma before the assembly

When it finally returned to me, the Kumma came by the same quiet route. This time, I was with my father, who managed to rendezvous his aunt during her women’s-trip-to-Muttrah Souq from Quriyat. Watching the scene of exchange, which took minutes as conversations, gifts and news were shared, under the souq’s gate as locals and tourists flow around them.

Phase V: ASSEMBLY

Seeing that I am still in Muttrah, I took the Kumma directly to the first Kumma tailor shop I passed by, as the final step is the stitching together of the circular crown and rectangular band. This can be done at almost any Kumma tailor shop across Muscat and takes less than a few minutes. Both times the tailors asked for mere change of a few hundred baizas, which I rounded up to 1 Rial.

Kumma tailor cutting the excess part of the crown

Kumma tailor inverting the Kumma as he then stitches the two parts together to complete the work

Final Thoughts

Much like tailoring a dishdasha or a suit, custom-making a clothing item you were daily in a colour you adore brings a quiet satisfaction.

But beyond the object itself, the process revealed something less tangible. The Kumma did not move through hands anonymously; it moved through people as friends and family. In some moments, collecting or delivering its parts became brief familial visits that turned into long-overdue exchanges that were otherwise rarely held in our busy lives.

What might otherwise have been a simple transaction became a shared act; something to do together rather than another visit marked only by formality. In that sense, the Kumma was not the only thing being tailored; it was also our relationships, our sense of community, and our flow towards the narrow streets and souq of old Muscat despite any of its modern expansions.

This process exists entirely outside industrial production models. It is social, communal, and deeply human. Products are created by people who know each other, for people they care about, in a natural timeline that is marked by visits and exchanges, or religious events not deadlines.

In an era dominated by speed, scale, and efficiency, the Kumma reminds us that design can also be slow, local, and made with love. Preserving this way of making is not necessarily for nostalgia, but about redefining design as a process that connects us, humans, together. And the best part? It leaves us with an object that carries evidence of the love.